Debunking LINQ-myths in .NET

There’s a lot of advice floating around about what you should and should not do when writing LINQ queries in .NET. But how much of that is actually (still) true? With .NET’s constantly evolving codebase, do certain best practices still hold up, or have they turned into myths waiting to be busted?

In this blog post, let’s debunk some common LINQ myths together! 👊🏻

🔮 Myth: Find is better than FirstOrDefault

Consider we have the following code:

List<int> numbers = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5];

var number1 = numbers.Find(x => x == 3);

var number2 = numbers.FirstOrDefault(x => x == 3);

Both Find and FirstOrDefault will perform the same result in this case, but people will tell you to always use Find over FirstOrDefault. This is one of the quotes I found online:

The Find method is generally faster than FirstOrDefault, because Find is specifically

designed for List and optimized for this collection type. It directly iterates over

the list and returns the first element that matches the predicate. The FirstOrDefault is a more general method that works on any IEnumerable. which can make it slightly slower due to enumerator overhead.

I’m leaving

SingleOrDefaultout of the equation here. That one would need to go through the entire collection in order to verify the predicate only matches once. This is obviously going to be slower thanFindorFirstOrDefault.

Hmm ok, so this seems to be legit, right? Let’s dig a little deeper. I’ll be running some benchmarks, and like always, I’ll be using BenchmarkDotNet. 🧪

I wrote the following benchmarks:

[MemoryDiagnoser(false)]

public class FirstOrDefaultBenchmark

{

private readonly List<int> _numbers = Enumerable.Range(1, 1000).ToList();

[Benchmark]

public int Find()

{

return _numbers.Find(x => x == 690);

}

[Benchmark]

public int FirstOrDefault()

{

return _numbers.FirstOrDefault(x => x == 690);

}

}

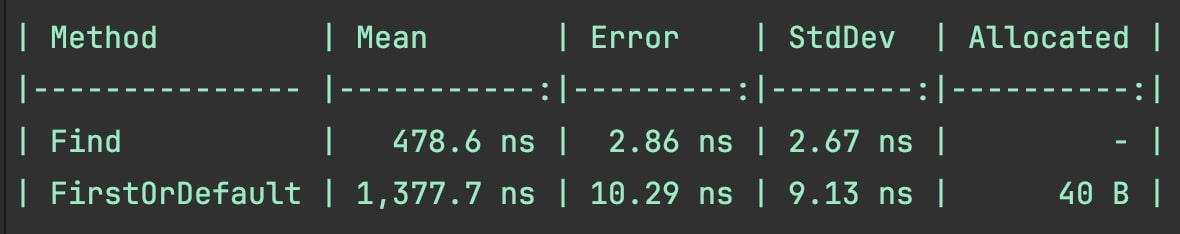

And here are the results:

Now ok, this seems to add up right? The FirstOrDefault method being three times slower than Find and also allocating some memory. Clearly the Find method is better, or is it? 🤔 I’m about to blow your mind.

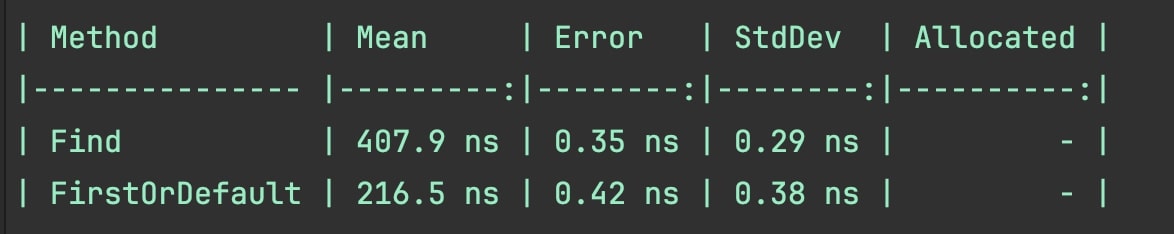

What I haven’t told you, is that this is running on .NET 8. Let’s switch to .NET 9, run the same benchmarks again, and see what happens.

Just by increasing the .NET version, the FirstOrDefault method is now actually twice as fast as the Find method and doesn’t allocate any memory anymore. Previously in .NET 8, the internal FirstOrDefault implementation was iterating over every item to see if it matched the predicate. Now in .NET 9, it will first try to convert the collection to a Span before starting the predicate matching. Spans are generally more performant than any other collection type. This explains the performance increase we’re seeing.

If you don’t fully understand Span as a concept, then this post on Medium gives a pretty good overview.

That’s our first myth busted! 💥 Let’s look at another one.

🔮 Myth: Use the Sort method instead of LINQ when sorting on primitive types

There are some people who say that using LINQ to sort primitive types is not a good idea. The main reason behind this is performance. Instead of using LINQ to do the sorting, we could use the Sort method instead:

var random = new Random();

var numbers = Enumerable.Range(0, 100).Select(_ => random.Next()).ToArray();

// Don't do this

var ordered = numbers.Order();

// Do this instead

Array.Sort(numbers);

This advice also counts when doing sorting on a List instead of an array. 💡 I also left

OrderByout of the equation, sinceOrderis already the LINQ optimization for sorting on primitive collections.

This video on YouTube from Nick Chapsas explains the reasoning behind it really well. I suggest you watch that video first if you want to know which benchmarks he did to prove this, and to understand the underlying concepts better. 🎬

Spoiler alert, this video was produced more than two years ago at the time of writing. This will be important for what I’m about to explain next.

It’s also important to point out that Array.Sort() will mutate the array, instead of returning a new one. That makes this method not a pure function. Personally, I’m not a big fan of that. I will always choose immutability over mutability if I have the option. But well, in this case, the Sort method will be more performant, as shown in the YouTube video, right? 🤔

So, I got curious and wanted to run those benchmarks for myself. I came up with the following benchmark:

[MemoryDiagnoser(false)]

public class OrderingBenchmark

{

// A seed is used to have deterministic results during benchmarking.

private readonly Random _random = new(123);

[Benchmark]

public List<int> Order()

{

var numbers = Enumerable.Range(0, 100).Select(_ => _random.Next());

return numbers.Order().ToList();

}

[Benchmark]

public List<int> Sort()

{

var numbers = Enumerable.Range(0, 100).Select(_ => _random.Next()).ToList();

numbers.Sort();

return numbers;

}

}

The benchmark was run against .NET 9. If you’re wondering why I recreate the collection everytime, it has to do with the fact that

numbers.Sortwill mutate the existing collection.

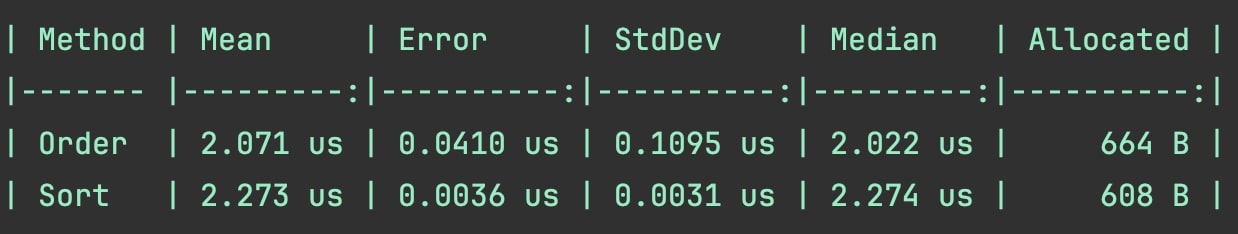

And here are the results:

Well well… would you look at that! I ran this benchmark 5 times, and it still holds up. While I have huge respect for a person like Nick Chapsas, it seems - at least on my computer - the benchmark results are pretty much the same. Only the memory consumption appears to be slightly higher for the Order method.

Now here we come to the conclusion that the YouTube video is already more than two years old. I truly believe this was a valid fact at a certain point in time, and Sort was significantly faster than Order. But right now, this doesn’t seem to be the case anymore. I will keep using Order, instead of switching to the Sort method.

As far as I’m concerned, that is our second myth busted! 👊🏻

🔮 Myth: Using LINQ lets us write better code

Now this is a very broad statement. Let’s first define what I understand under ‘better code’. There are generally speaking two factors for me:

- Code that is more readable than its counterpart

- Code that is more performant than its counterpart

There are more of course, but you can consider those two to be already pretty important when it comes to writing good code.

I think a lot of you - myself included - will probably choose to write LINQ over its counterpart. And who can blame us? In most cases, it’s easier to write, and easier to read. But is it also more performant? 🤔 Not necessarily.

Let’s take one such use case where we need to retrieve the last person from a collection. ☝🏻

// Don't do this

var personA = person.Last()

// Rather do this!

var personB = person[^1]

The

^1you see is syntactic sugar. When this compiles to IL code, it will translate tocount - 1. Which just means it will take the last item in the list based on the index.

I’m going to run a benchmark on this. Spoiler alert, the relative difference in performance between the two is quite shocking.

[MemoryDiagnoser(false)]

public class ToLINQOrNotToLINQBenchmark

{

private readonly List<Person> _persons = new();

public ToLINQOrNotToLINQBenchmark()

{

for (var i = 0; i < 100_000; i++)

{

_persons.Add(new Person { Id = i });

}

}

[Benchmark]

public Person GetLastPersonWithLINQ()

{

return _persons.Last();

}

[Benchmark]

public Person GetLastPersonWithoutLINQ()

{

return _persons[^1];

}

}

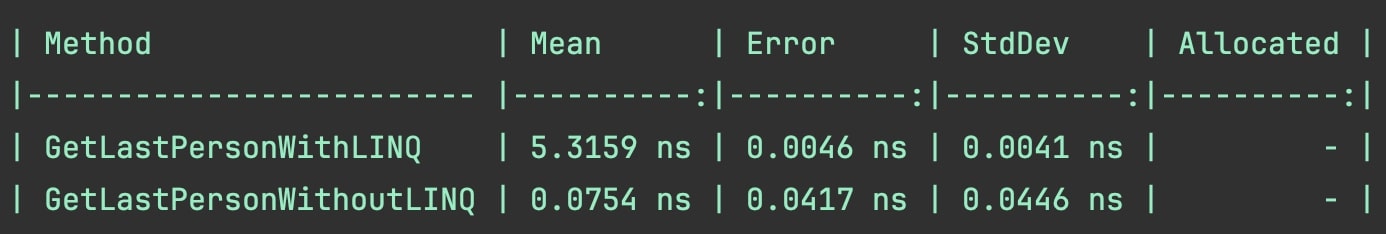

And here are the results

On my computer, this results in a 70x performance boost when not using LINQ!

Now why is there such a huge difference here? There are several reasons, but there is one that stands out. Most of the LINQ methods you encounter, are written as an extension method on the IEnumerable interface. When performing something like Last(), the internal logic first needs to determine what concrete type of collection you have, so that it can find the most optimal way for getting that last item.

This is a little ironic, since talking about optimizations here, doesn’t really make sense in the broader context. If you already know your concrete type of collection, then why not do the index accessor straight away? If we’re really talking about optimization, as you saw in the benchmarks, then that is still going to be much more performant than the ‘optimized’ generic approach of the LINQ method.

One benefit of having LINQ is that it will check against some common cases. For example, what if the collection is null or empty? It will still throw exceptions in these cases, but with a little more context than you would have if those exceptions occurred implicitly. For me personally, this does not outweigh the performance benefit. If you are really concerned about not having these checks, you can add them yourself, and it would still be more performant than choosing LINQ.

I think we can safely debunk this myth as well 👊🏻. LINQ might be more or as readable as normal code, but it definitely doesn’t win any medals in the performance category.

So, what can we take away from this? Besides the fact that not everything you read online is true, it’s also important to be aware of outdated information. Some facts may have been accurate when they were first published, but are no longer valid today.

Credits

Even though Nick Chapsas’ video about not using LINQ to sort primitive collections is no longer entirely accurate, I still owe him credit for much of my inspiration:

- Stop Using FirstOrDefault in .NET! | Code Cop #021

- Stop using LINQ to order your primitive collections in C#

- Like said before, this one is not completely true anymore.

- When LINQ Makes You Write Worse .NET Code

If you liked this blog post, be sure to also take a look at his YouTube channel as well! 🎬